Introduction to Literature

by: Professor Jason Whitesitt, Yavapai College

Let’s begin with a pop

quiz. Below are two statements. I would like you to please examine each and

then determine the most important difference between them.

I.

Two plus two

equals four.

II.

The tale of

Cinderella reinforces an androcentric worldview in which women are treated as

exchangeable commodities.

Think about this now –don’t

just speed ahead for the easy answer. In

fact, thinking for yourself is part of the quiz. Got an idea?

Think you know?

As you may have determined,

the first line is a statement of truth.

Two plus two equals four. This is

a fact. You can ask your math professor.

You can ask any math professor. You can ask your ten-year-old cousin. Modern science is predicated on this sort of

thing and there is really no room to argue.

Statement two, however, is an opinion.

It may be an educated opinion, an informed opinion, but it is still only

an opinion. This may seem elementary, but this is an incredibly important distinction to make before one

goes mucking about in world literature. Despite

what that one pompous or insecure English teacher told you, there is no single

answer to any given text. Too many

people think that this sole epiphany exists in every work and that if they

don’t get it, then they’re stupid. Yet,

interpreting literature is an art and not a science, and so there are multiple

avenues of approach and a number of ways of being right. How liberating! Indeed, it is so liberating that I want you

to stand up, right now, wherever you are and shout: LITEARATURE IS LIBERATING! Go ahead and do it. No, really.

This is important (the ghosts of eccentric professors past are watching

you). There. Feel silly?

Feel loosened up? Good. This is a nice start.

Literature is liberating and so you should be using

your own experiences, your own ideas, your own lamplight of reason to craft

interpretations. However, know that any

given interpretation is only as good as the textual evidence used to back it

up. You need to ground your theories in

the actual words of the work. If you

want to assert that Romeo was really a Medici spy trying to seduce the launch

codes for a Renaissance WMD out of Juliet . . . Well, I’m not going to say

you’re wrong. Instead, I’m going to ask

you to prove it. Comb through the play

and produce the evidence. Show me the

lines, point out the symbols, analyze the theme. In other words, do the work and you can’t be

wrong. How great is that?

Now that you are loose and

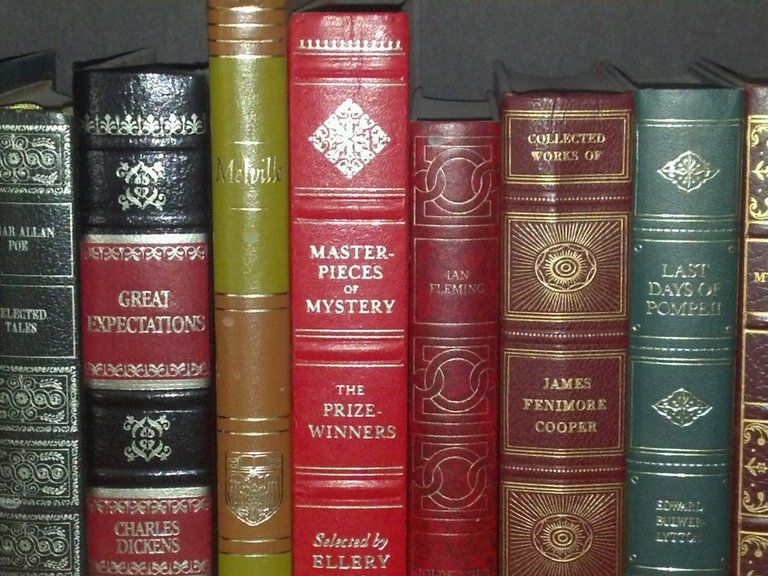

liberated let’s talk about the types of literature. If you’ve ever walked into a Barnes and Noble

or prowled the racks of your local library, you probably know that not all

books are the same. There’s the stuff

you read for information (mostly nonfiction, and not our concern in this

class), there’s the stuff you read for pure pleasure (literature with a little

"l"), and there’s the stuff you read in classes like this (Literature

with a capital "L").

This sort of reading rarely challenges your ideas about the world. In fact, it usually reinforces the things we'd all like to think are true: everything happens for a reason, the good are rewarded and the evil suffer, everything comes out okay in the end. You may have noticed that most of these books have happy endings. When they don't, you cry along with the characters, but their sad fates don't make you question the order of the universe. Those who die, die for a clear and logical reason.

Literature with a capital "L" is different. It demands more of you. It requires both your attention and your participation. It asks you to think, to analyze, to stop occasionally in the middle and ask, “Why did that happen?” or “What is he doing in this scene?” Many of these works make you uncomfortable. They make you question your biased and easy assumptions about the world and your place in it. And sometimes there’s not a happy ending.

In return, Literature helps you grow. It allows you to experience events emotionally and intellectually without having to suffer the physical danger. You get to experience Dark Age Denmark without worrying that you will be Grendel’s next meal. You get to visit Colonial Jamaica without catching malaria. You get to ride in an Indian cab with a murderer and not fear for your life. You get to look into the hearts and minds of the characters and take home for free what they teach you about yourself, your family, and the world.

Everything in this class is designed to enhance that experience--to help you learn to read more effectively, so that you can experience Literature more fully, and enjoy it more.

And any reader will tell you, that’s the point of all this: enjoyment. I can’t promise you that any of the information you receive in this class will ever make you a dime. I seriously doubt that any Human Resources director is going to look at your resume and say, "Oh! Here’s someone who's read Things Fall Apart! Let’s hire him!” Your gains will be less tangible: an enhanced ability to see things from other points of view, to detect patterns in people’s actions, to have a deeper understanding of the complexities of human motivation, to widen your knowledge of the world’s people and cultures. This might not put food on the table but is should feed your soul, heart, and mind.

No comments:

Post a Comment